A couple of weeks ago, Katrina Pacey and I had the opportunity to present a workshop on harm reduction to group of about 25 women working in transition houses around the province.

We arrived at the BC Society of Transition Houses conference prepared to give a talk that we naively thought would be an introduction to the subject of substance use and public health. What we found, was a room full of women with a deep understanding of the interplay between trauma and addiction in the lives of some of the women they work with, the dire impacts of criminalization and other punitive responses to substance use and the need for harm reduction and treatment services to be integrated into the healthcare infrastructure of their communities. In the end, the workshop was more of a dialogue, and we learned as much as anyone in the room.

Get Updates

Using the law as a catalyst for positive social change, Pivot Legal Society works to improve the lives of marginalized communities.

Upon closer reflection, it should not be surprising that women working in transition houses had so much insight into harm reduction as a philosophy and as a practice. The transition house movement was born out of a broader feminist enterprise focused on challenging deeply  embedded myths, stereotypes, and a broader cultural context that assigns power, resources and rights in highly discriminatory ways. This movement politicized what were generally considered to be private matters and developed services that put the woman at the centre. Developed though decades of analysis grounded in practices, many of the principals that underlie feminist activism have a lot to offer the movement for effective drug policy and treatment.

embedded myths, stereotypes, and a broader cultural context that assigns power, resources and rights in highly discriminatory ways. This movement politicized what were generally considered to be private matters and developed services that put the woman at the centre. Developed though decades of analysis grounded in practices, many of the principals that underlie feminist activism have a lot to offer the movement for effective drug policy and treatment.

• The right to safety

At the core of all feminist anti-violence work is a bold assertion: everyone has a right to safety. Feminist safety planning means putting the woman at the centre of the safety plan and recognizing women as experts in their own lives. It entails recognizing that we can support a woman to mitigate risks no matter where she is in the cycle of staying, leaving and returning that often characterizes violence relationships and building the trust needed to create safety plans that actually work for women in practice.

• Attitudes that cast blame and intensify stigma do not promote safety or change

Feminists know that the harms of living in an abusive relationship or otherwise experiencing gendered violence are magnified when women are met with judgmental attitudes and belief systems. In our workshop we looked at some of the common statements we hear about women who use substances:

“She has been offered help so many times before, but she just keeps going back”.

“She cares about drugs more than her kids”.

“She is so weak and needy”.

“Maybe she will learn when she wakes up in the hospital”.

“I don’t think she even wants to be healthy”.

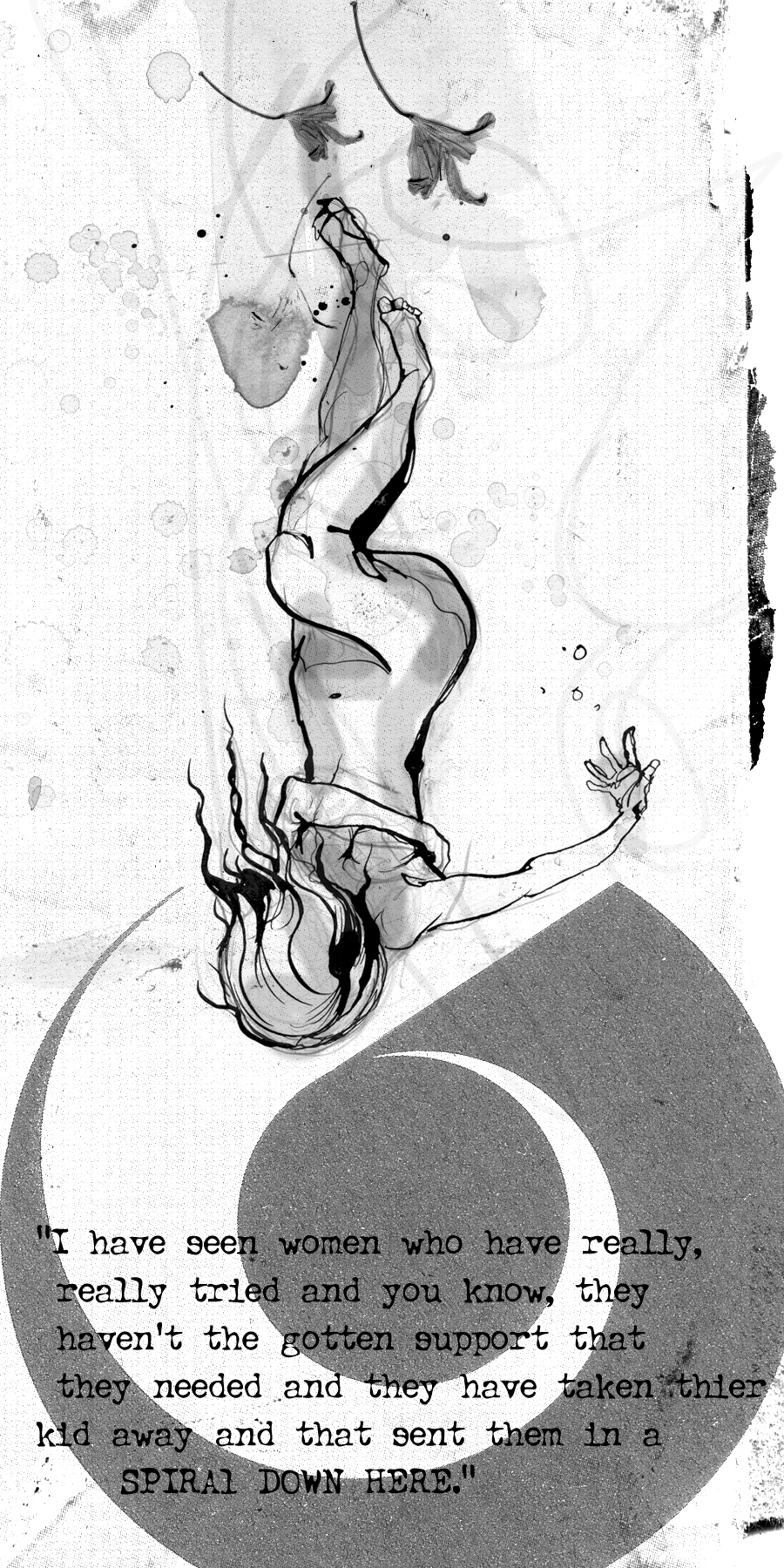

The commonality with the attitudes and beliefs the transition house movement has been combatting for decades was not lost on anyone in the room. The process has not be easy, but because of their work we are slowly getting to a place where women who experience violence are no longer pathologized as weak, reckless or child-like, as the dynamics, economic realties and belief systems that enable gendered violence become more widely understood.

• The personal is political

The feminist movement coined the phrase, and since then, feminists have been working tirelessly to make it a reality. From violence in the home, to reproductive right, to childcare, feminists have pushed our understanding of what constitutes a social issue, overturned unjust laws and highlighted our collective responsibility for ending inequality and preventing harms.

The transition house workers we met are working with a diverse community of women, including women struggling with substance use, and it was clear how under-resourced their communities are in terms of harm reduction and addiction treatment services. But this workshop left me with a strong sense of their collective commitment to effectively serve women who use substances. It also left me with a strong sense that feminist organizations that combine direct service delivery with a political mission have a lot to offer the growing movement for harm reduction and drug policy reform.